Mercury, world of extremes

Why We Study Mercury

Mercury doesn't always receive a lot of attention. The innermost planet to the Sun is smaller than both Jupiter’s moon Ganymede and Saturn’s moon Titan. It has been overshadowed by worlds like Mars that may have once harbored life, and planets that are solar systems unto themselves like Jupiter and Saturn.

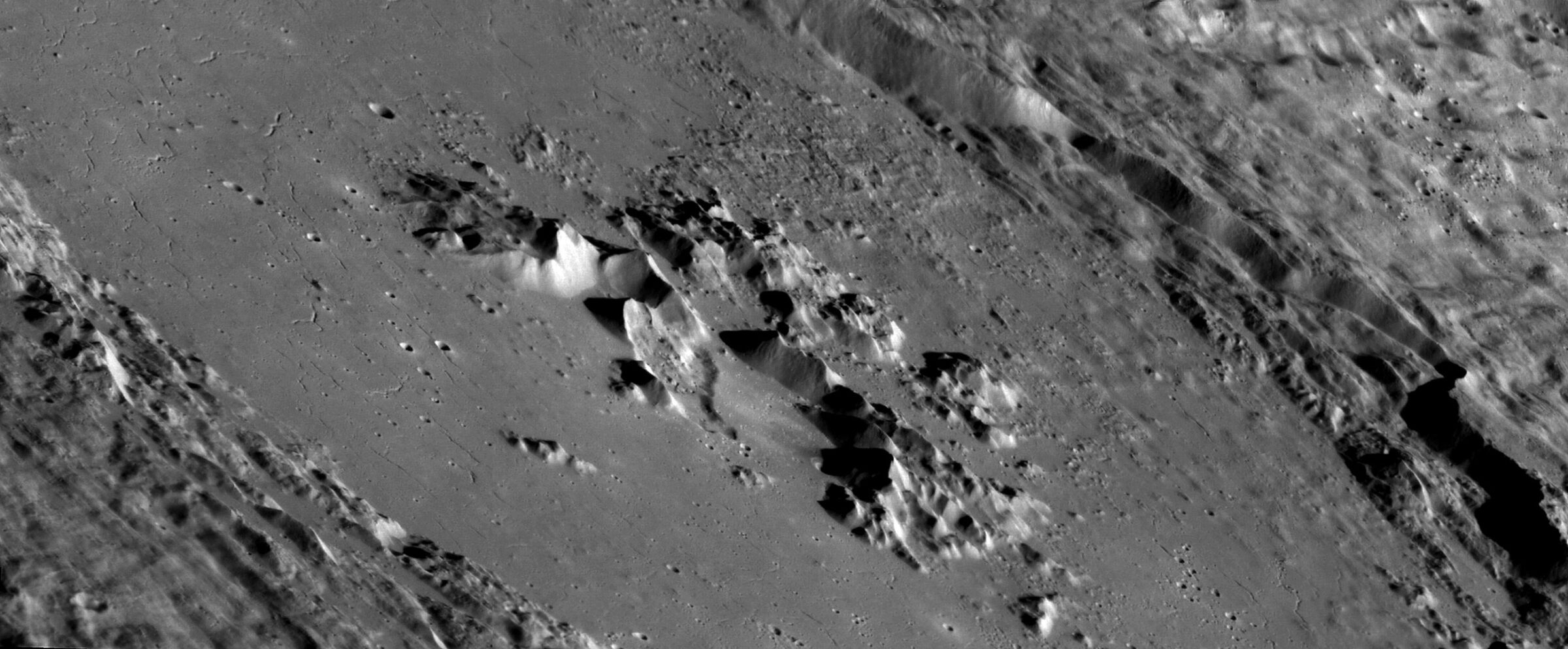

Mercury is a world of extremes. Its surface appears old, cratered, and undisturbed by recent geologic activity. Yet it has a magnetic field, which is normally caused by a molten core that should, in turn, cause surface changes. Thanks to the nearby Sun, Mercury’s surface temperatures reach 430 degrees Celsius (800 degrees Fahrenheit) — yet like our Moon, water ice exists inside permanently shadowed craters at the poles.

Mercury is particularly interesting to scientists who study exoplanets, planets that orbit other stars. Thousands of known exoplanets orbit extremely close to their stars. By studying Mercury right here in our backyard, we can better understand what these close-orbiting worlds might be like.

Scientists aren't sure why Mercury’s core makes up 85% of the planet’s volume — much more than Earth’s, which makes up just 15%. The answer may help us understand the possibilities for different types of planets and how our solar system evolved.

Mercury Facts

Surface temperature: -184°C (-300°F) to 465°C (869°F)

Average distance from Sun: 58 million km (36 million miles), or 61% closer to the Sun than Earth

Diameter: 4,879 km (3,032 miles), Earth is 2.6 times wider

Volume: 61 billion km3 (15 billion mi3), Mercury could fit inside Earth 16.4 times

Gravity: 3.7 m/s², 38% of Earth’s

Solar day: 176 Earth days

Solar year: 88 Earth days

Atmosphere: Negligible

How We Study Mercury

Studying Mercury is a challenge because it actually takes more energy for a spacecraft to reach Mercury than Pluto. Mercury is the fastest-orbiting planet in our solar system — it blazes around the Sun at 48 kilometers (30 miles) per second. Missions trying to enter orbit there typically fly past Earth, Venus, and/or Mercury itself, using gravitational nudges to adjust their trajectories.

Only three spacecraft have ever visited Mercury. In the 1970s, NASA’s Mariner 10 made three flybys of the planet — seeing the same side each time — revealing its crater-ridden surface and magnetic field. No spacecraft visited again until NASA’s MESSENGER became the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury in 2011.

MESSENGER gave us a more complete picture of the planet than ever before. The spacecraft revealed Mercury to have an unusually large core and an offset magnetic field. MESSENGER also found the planet to be surprisingly rich in volatiles, elements that evaporate at room temperature, including finding ample evidence of water ice on Mercury’s poles. This helped scientists rule out many of its previously suggested formation models while also advancing our knowledge of how the solar system formed and evolved.

We also study Mercury using powerful Earth-based radar telescopes, which zap the planet with energy and measure the reflections. The Arecibo Observatory radio telescope created maps of water ice inside Mercury’s permanently shadowed craters.

The only current Mercury mission is BepiColombo, a joint Japanese-European mission that launched in 2018 and will arrive in Mercury orbit in 2025. BepiColombo will help us understand why Mercury has such a large core, and how the planet generates its magnetic field. BepiColombo will also allow planetary scientists to better understand why some planets have internally generated magnetic fields (Mercury and Earth) while others don’t (Venus and Mars). On Earth, our magnetic field protects us from the solar wind, which would otherwise damage our planet’s atmosphere.

Action Center

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth